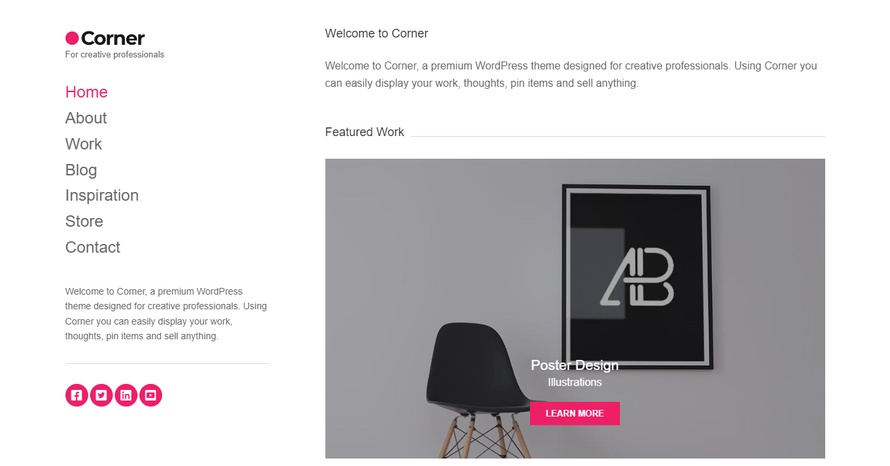

Corner 1.1.1 is available for download

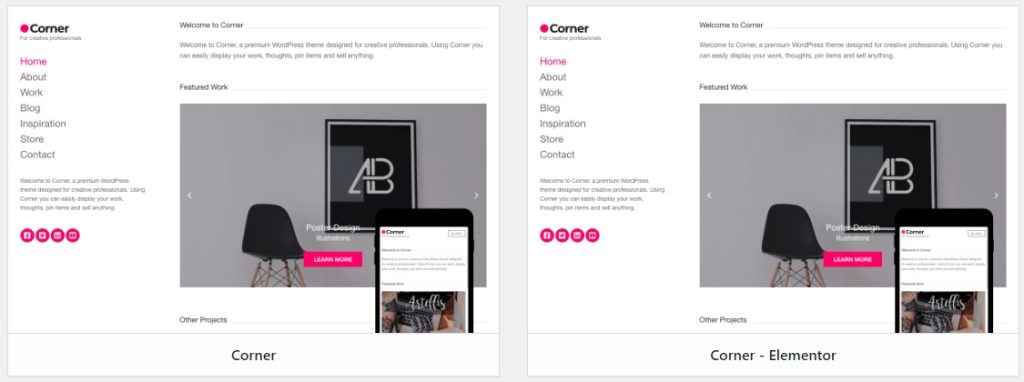

We’d like to let you know that Corner has received an update which improves its Elementor integration and fixes small issues.

With this update we have simplified the process of importing sample content from the theme’s Elementor demo, allowing for a smoother website setup. The import process is handled by the popular One Click Demo Import plugin.

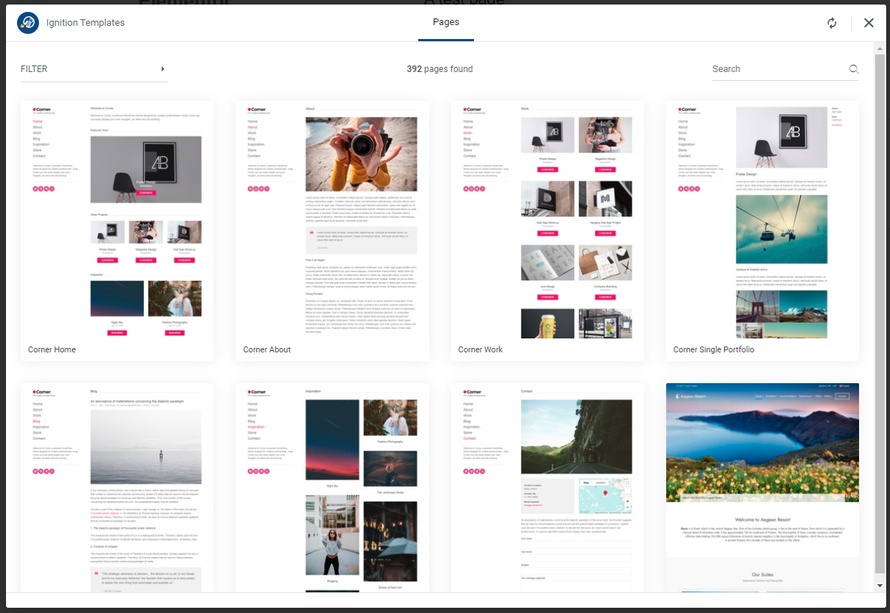

In addition, Corner now offers the option to import pre-designed pages as Elementor templates. By utilizing the CSSIgniter Connector plugin, you can conveniently access and customize these templates, enabling you to craft a personalized online portfolio that echoes your creative identity.

Furthermore, this update includes subtle styling improvements and minor fixes to ensure seamless performance and an optimal user experience. For a comprehensive overview of changes, kindly refer to the theme’s changelog.

Along with Corner the Ignition Elementor Widgets plugin has received an update which adds masonry layout support to the Post Types widget as seen on the theme’s demo.

Explore the potential of Corner to create an engaging online portfolio that resonates with your creative endeavors. Showcase your projects with authenticity and style, capturing the essence of your creative expression. With Corner, enhance your online presence and engage your audience on your terms.