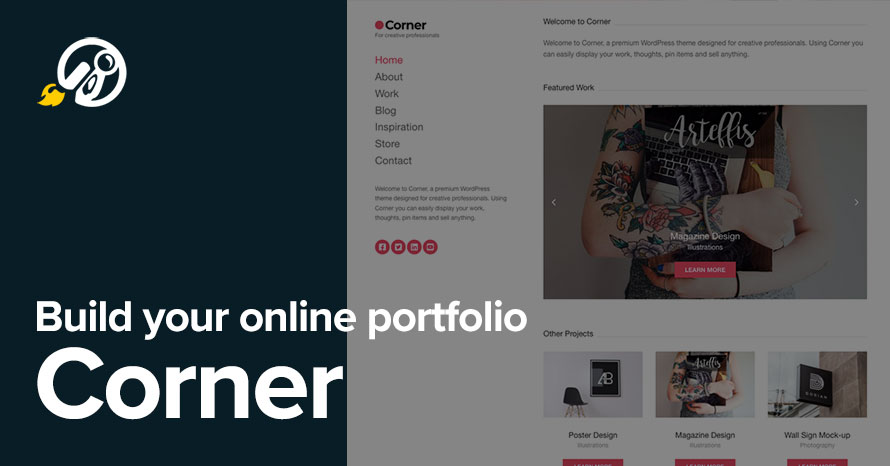

Build your online portfolio with Corner

Say hello to the updated version of our popular portfolio theme, Corner. The theme is now based on our Ignition Framework offering you all the flexibility and customization options you need to create a great online portfolio to showcase and even sell your work. Let’s take a look at some key features.

Solid Foundation

The new version of Corner takes full advantage of our robust and flexible Ignition Framework. The framework comes in the form of a separate plugin and is responsible for all the available customization options for layout, colors, typography and more, it also carries the custom post types, all necessary custom templates and compatibility code for third party plugin integration. This delegation of duties allows the plugin to handle just the appearance of the site making it lightweight, fast and very easy to work with and modify. Furthermore the standalone nature of the plugin allows for faster updates to fix bugs, add new features and restore compatibility when needed.

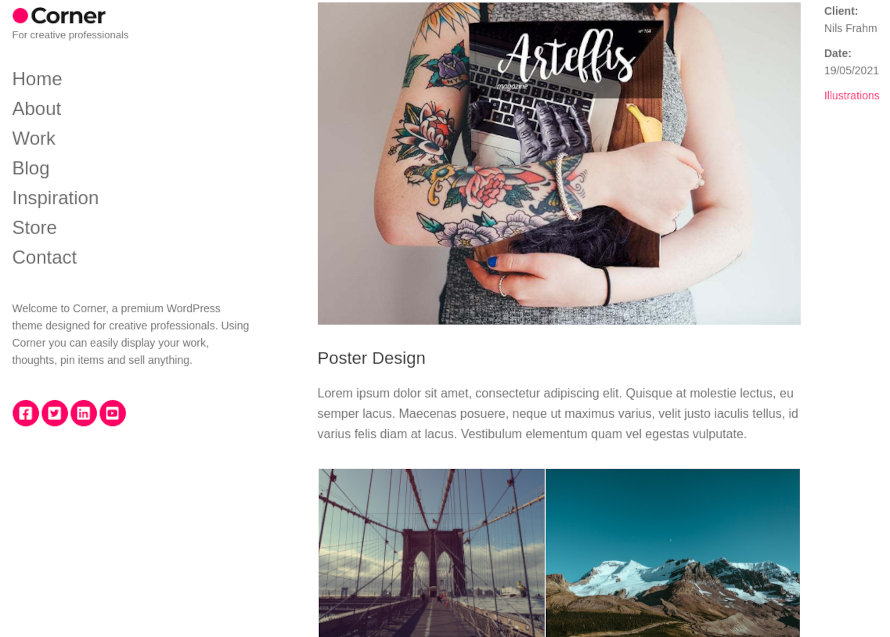

Portfolio Management

Corner takes full advantage of the Portfolio custom post type built into the Ignition Framework to create perfect showcases for any sort of creative work. The custom post type is fully compatible with the WordPress block editor and popular page builders to give unparalleled flexibility when it comes to content creation and layout generation in order to best present your work. With the use of the Post Types block built into GutenBee, our free custom blocks plugin, you can easily create portfolio grids with variable column numbers, optional pagination and category filtering to allow you visitors to easily locate a certain piece of work they are looking for.

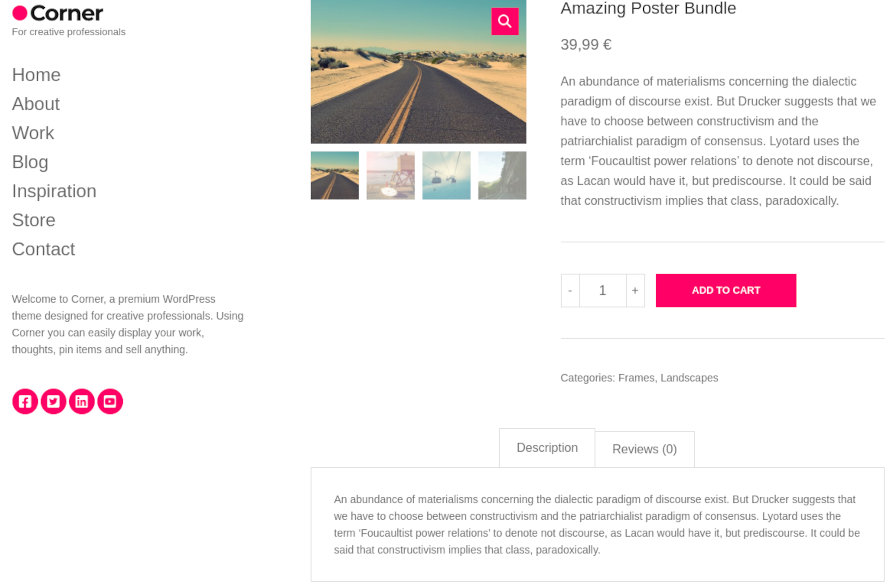

WooCommerce Ready

Corner offers WooCommerce compatibility right out of the box. With all the features of the most popular eCommerce plugin for WordPress at your disposal you can have your online store up and running in no time. Sell any kind of products whether physical or digital, you can even handle workshops and online seminars, all through your own site.

Flexible Layouts

Among the dozens of customization options offered by Corner you have the ability to change the site’s entire layout through a simple drop down. Pick whether you want a full width or a boxed layout for your site, with an easily customizable site width, align the content, toggle the content sidebar and many more to achieve the perfect appearance for your content.

Wrapping up

Corner is the perfect theme for your next online portfolio website. Create perfect layouts for each of your portfolio items using the built in custom post type and have portfolio listings up in no time with our custom Post Types block. If you are planning to sell your work through your site Corner’s WooCommerce compatibility can take care of that as well. Learn more about the theme and grab your copy in the links below.