Knowledge base

Categories

The Ignition Framework

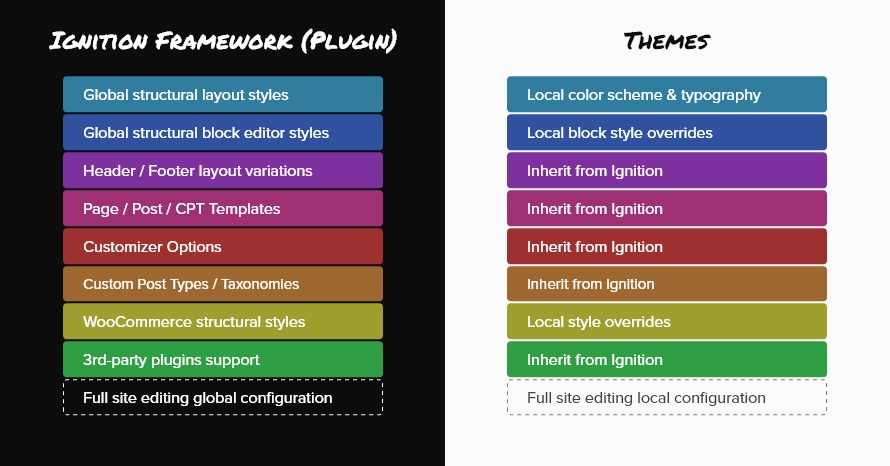

The Ignition Framework was born out of necessity to make managing our theme library easier and more efficient. When each theme is its own entity adding new features, patching vulnerabilities, fixing bugs and ensuring compatibility with popular plugins like WooCommerce is a daunting task, we needed a solution which would streamline the whole process. This solution was the Ignition Framework.

The Ignition Framework comes in the form of a standard WordPress plugin. This singular plugin carries all needed functionality to help users create beautiful and flexible WordPress-based sites using our themes. Each theme now only handles one thing, the site’s appearance by providing the necessary styling. In the list below you can find a few key aspects handled by the plugin.

- Global layout styles, leaving just color scheme & typography to the theme.

- Global block editor styling, the theme just overrides block styling where needed to match its specific design.

- Header and footer layouts.

- Post, page and custom post type templates.

- All the customization options found in the Customizer such as color options, typography options, header & blog layout options and more.

- Custom post types and their taxonomies, for example the Accommodation post type in Aegean Resort.

- WooCommerce structural styling, leaving appearance related overrides to the theme.

- All third party plugin integrations needed by our themes.

- In future updates, the framework will also handle the global configuration for the full site editing experience.

The fact that the plugin handles pretty much everything apart from styling makes it very easy to incorporate new features, fix bugs and update compatibility with third party plugins easily and very quickly due to the fact that changes need to be made in just one place and then deployed to all framework based themes with a single update.

Getting started

To get started with the Ignition Framework and the themes based on it, you need to first get them installed.

Install the Ignition Framework Plugin.

Install an Ignition Framework Theme.

You can install the plugin and a theme in any order you like, just make sure both are installed and activated.

To get a solid base to build your site upon you can easily import the theme’s sample content.

If you plan to modify templates, add functionality and modify the theme’s styling install a child theme to preserve your modifications across updates.

You can find a list with all the Ignition Framework based themes here.

Customizing a theme

Framework based themes feature dozens of customization options built in the WordPress Customizer. Customize the theme’s layout, colors, typography and many more to create the perfect website according to your needs.

Apart from global customization the appearance of single items can be tailored to your needs by changing their header, hero, breadcrumbs and more.

WooCommerce compatibility

All framework based themes are compatible with WooCommerce out of the box. The appearance of the store can also be modified via the theme’s Customizer Options.

Custom post types

Seven custom post types are built in the Ignition Framework. Six of them are used in various combinations in each theme to help with data categorization. These are: Accommodation, discography, event, portfolio, service and team. By default each theme has only the custom post types needed to provide its functionality enabled, all other are disabled. However users can enable or disable custom post types at will.

The seventh custom post type is global sections which is enabled by default on all themes. With global sections users can create reusable content using the block editor or their favorite page builder.

Other features

All themes feature RTL compatibility with custom styles which can be extended via child themes.

Finally, a feature very handy for developers, framework themes come with dozens of action hooks which can be used to display content on a multitude of theme locations.